Ojibwa

Ojibwa (Ojibwe, Ojibway) belongs to the Ojibwa-Potawatomi group of the Algonquian branch of the Algic language family. Speakers of Ojibwa call it Anishinaabemowin or Ojibwemowin. It is a macrolanguage comprised of a number of autonomous varieties with no standard writing system. Several varieties of Ojibwa are spoken in Canada from Quebec, through Ontario, Manitoba and parts of Saskatchewan, with outlying communities in Alberta. Ojibwa is the third most spoken language cluster in Canada, after Inuktitut and Cree. In the U.S. Ojibwa is the most commonly spoken aboriginal language after Navajo and Cree. Varieties of Ojibwa are spoken in the U.S. from Michigan through Wisconsin and Minnesota, with a number of outlying communities in North Dakota, Montana, Kansas and Oklahoma.

Status

Ojibwa served as a lingua franca across Canada and in the northern U.S. during the fur trade. Today, it is one of the more robust North American Native languages with efforts being made to revitalize it through multifaceted approaches that include immersion schools in which children are taught in Ojibwa.

Dialects

There are some differences in the classification of Ojibwa varieties.

Structure

Sound system

Vowels

Ojibwa dialects tend to have three short and four long vowels. Long vowels below are marked with a macron. The long vowel /ē? lack a corresponding short one. Some varieties of Ojibwa also have nasal vowels (Wikipedia). Some dialects of Ojibwa drop unstressed vowels, e.g, in the Odaawaa dialect, Anishinaabemowin becomes Nishnaabemwin.

| Close |

i, ī

|

||

| Mid |

ē

|

o, ō

|

|

| Open |

a, ā

|

Consonants

Ojibwa dialects usually have 17 consonants. Stops, fricatives and afffricates can be either voiced or voiceless. Voiceless consonants are often aspirated or preaspirated. The semivowel /w/ is pronounced with very little lip rounding. The glottal fricative /h/ occurs in some dialects instead of the glottal stop /?/ (Wikipedia). Ojibwe allows few consonant clusters, mostly in the middle or at the end of words. The voiceless glottal fricative /h/ is only in a small number of words.

| Palatal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | voiceless |

p

|

t

|

k

|

ʔ

|

||

| voiced |

b

|

d

|

. |

g

|

. | ||

| Fricatives | voiceless |

s

|

ʃ

|

(h)

|

|||

| voiced | . |

z

|

ʒ

|

. | . | ||

| Affricates | voiceless |

tʃ

|

|||||

| voiced | . |

dʒ

|

. | . | |||

| Nasals |

m

|

n

|

. | ||||

| Approximants |

w

|

j

|

|||||

- /ʔ/ = similar to the sound between the vowels in uh-oh

- /ʃ/ = sh in shop

- /ʒ/ = s in treasure

- /tʃ/ = ch in chap

- /dʒ/ = j in job

Metrical feet

Ojibwa words are divided into metrical feet. Every two syllables constitute a foot, starting with the beginning of a word. The first syllable in a foot is weak, the second one is strong. Long vowels are always strong. When they occur in the weak position of a foot, they form a separate one-syllable foot, and counting continues starting with the following vowel. In an example from Wikipedia, the word bebezhigooganzhii ‘ horse’, is divided into feet as follows: (be)(be)(zhi-goo)(gan-zhii).

Grammar

- Like many other polysynthetic aboriginal North American languages, Ojibwa attaches prefixes and suffixes to roots to form long words that in other languages might constitute a whole sentence. For instance, the word aniibiishaabookewininiiwiwag means ‘they are Chinese’ (example from Wikipedia).

- Ojibwa is an ergative language. Ergative languages mark the subject of a transitive verb with the ergative case. They mark both the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb with the absolutive case.

Nouns

- Ojibwa distinguishes between animate and inanimate nouns. Animate nouns include persons and animals, as well as objects of spiritual significance.

- Nouns are marked for number: singular and plural.

Adjectives

- Instead of adjectives, Ojibwa uses verbs which function as adjectives, e.g., ozhaawashkwaa waabigwan, literally ‘the flower blues’, i.e., ‘blue flower’ (example from Wikipedia).

Pronouns

Pronouns are marked for the following categories:

- Number: singular and plural;

- Person: first, second, and third;

- There is a distinction between a third person who is nearer (proximate) and one that is further (obviative).

- There is a distinction between inclusive and exclusive first person plural. An inclusive ‘we’ includes the addressee. An exclusive ‘we’ does not.

Verbs

- Verbs agree with their subjects in person, number, and animacy.

- Verbs belong to four classes: transitive verbs with animate objects, transitive verbs with inanimate objects, intransitive verbs with animate objects, and intransitive verbs with inanimate objects.

- Ojibwa verbs use prefixes to mark past and future tense.

- A variety of of prefixes is used to convey additional information about an action, e.g., the verb root –batoo ‘to run’ combines with the prefix bimi– ‘along’ to form the verb bimibatoo ‘to run along’.

- Ojibwa verbs have three ‘orders’ that more or less correspond to mood in European languages: the Independent Order corresponds to the indicative mood; the Conjunct Order is used mostly in subordinate clauses; the Imperative Order corresponds to the imperative mood.

- There are two imperatives: an immediate imperative (do something right away), and delayed imperative (do something later).

- Adverbials indicating motion, e.g., ‘towards’, are incorporated into the verb stem, while temporal adverbials, such as ‘today’, are independent words.

Word order

Subjects and objects in Ojibwa can either precede or follow the verb, depending on the focus (the more important information) in the sentence. The more important information precedes the verb, the less important information follows it.

Vocabulary

Ojibwa tends not to borrow words from other languages. Instead, it creates new words by using native elements. For instance, bemisemagak ‘airplane’ literally means ‘thing that flies’. However, there exist a few borrowing from other indigenous languages, especially Cree, from English, e.g., gaapi ‘coffee’, and from French, e.g., boozhoo ‘bonjour’.

Below are a few basic words and phrases in Ojibwa.

| Hello | boozhoo (from French bonjour) |

| See you later | baamaapii |

| Thank you | miigwech |

| Please | daga |

| Yes | en’ |

| No | gaawiin |

| Man | Nini |

| Woman | Ikwe |

Below are Ojibwa numerals 1-10.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| peezhig | niinz | niso | niiwin | naanan | ningotwaaso | niinzwaaso | niswaaso | saangaso | mitaaso |

Writing

There is no standard orthography for writing Ojibwa.

- In the U.S., Ojibwa is usually written with the Roman alphabet. There are several Romanized systems for writing the language (Wikipedia). The newest Roman character-based writing system is the Double Vowel System. In this system, long vowels are written with double vowel symbols, e.g., a long /a/ is written as aa. The Double Vowel System is quickly becoming accepted due to its ease, especially in computer applications.

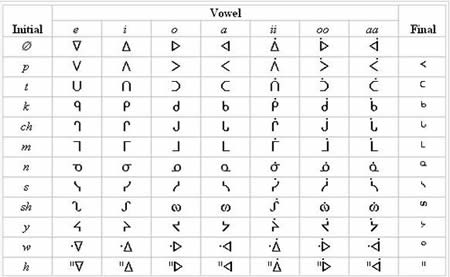

- In Canada, Ojibwa is written in Canadian Aboriginal syllabic writing, or simply syllabics. Syllabics have also been occasionally used in the U.S. by border communities. Below is a table of Ojibwa syllabics (from Wikipedia).

Take a look at Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Northwestern Ojibwa.

|

ᐅᔑᐱᐃᑲᓐ ᐯᔑᒃ |

| Kakenawenen kapimatisiwat nitawikiwak tipenimitisowinik mina tapita kiciinetakosiwin kaye tepaketakosiwin. Otayanawa mikawiwin kaye nipwakawin minawa tash ciishikanawapatiwapan acako minowicieitiwinik. |

| Article 1 All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Did You Know?

American English is thought to have borrowed these words from Ojibwa.

|

chipmunk |

from Algonquian (probably Ojibwa) ajidamoo (in the Ottawa dialect ajidamoonh) ‘red squirrel’ |

|

totem |

from Algonquian (probably Ojibwa) odoodeman ‘his sibling kin, his group or family,’ hence, ‘his family mark’ |

|

Mississippi |

from Algonquian (probably Ojibwa) mshi– ‘big,’ ziibi ‘river’ |

Difficulty

There is no data on the difficulty of Ojibwa for speakers of English.